When democratisation in developing countries is discussed, the focus is often on the right to vote and how the government’s power stems from an elected parliament. However, even if these criteria are fulfilled, it is not unusual that elections are marked by fraud and corruption, something that democracies in the western world are not slow to point out.

“Even though we criticise election fraud in less developed countries, we don’t really know very much about what has happened here historically and why we have succeeded in having free and fair elections. My study is about gaining a better understanding of our own development”, says Professor of Political Science Jan Teorell.

Sweden also happens to be a particularly interesting example, considers Teorell, as fair elections could be conducted right from the introduction of democracy in the early 1900s. Furthermore, it is an easy country to study, as there are good archives available going back hundreds of years.

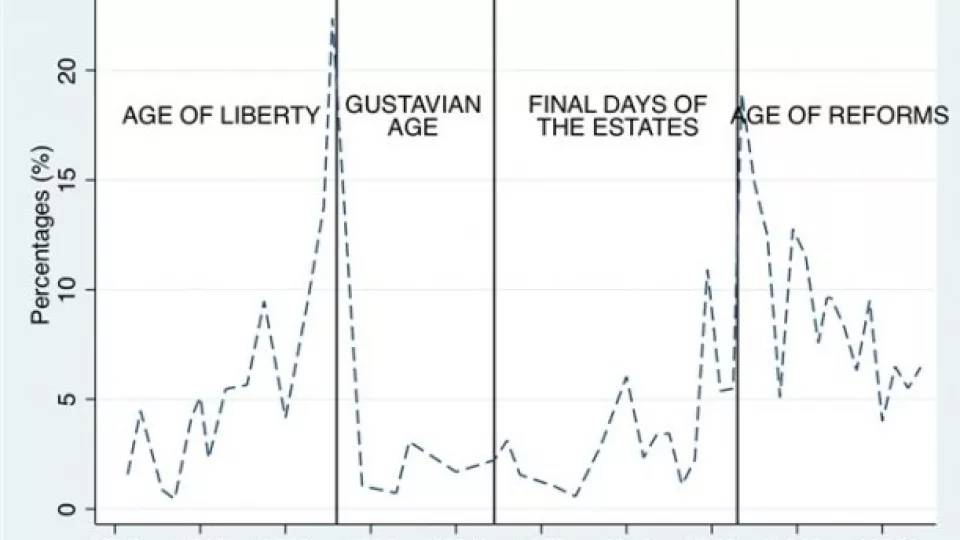

The study focuses on the years between 1719, at the start of the Age of Liberty when the royal autocracy was temporarily abolished, and 1908, when the last election was held before proportional representation was introduced in Sweden. A total of 54 parliamentary elections were held during this period. All of these were followed by a greater or lesser number of petitions from citizens who claimed that the election had not been conducted properly.

Political science research usually points to four important factors that prevent election fraud:

- Secret ballots

- The election system – proportional representation elections present less risk of electoral fraud than majority elections in single-member constituencies.

- Economic welfare – it is easier to bribe the poor than the rich.

- Land reforms – power concentrated among a few landowners is considered to pave the way for corruption.

However, none of the factors above apply to the Swedish case, according to Jan Teorell. Instead, it is the professionalisation of the bureaucracy and the power of the political parties that influenced election fraud – but in completely different ways. Professional bureaucrats, appointed on merit rather than on political grounds, counteract election fraud. Strong political parties influence elections in the entirely opposite direction.

“When parties compete for power there is a lot more at stake, because the parties are better at organising different interests from other parts of the country, and the election battle becomes more ideological”, says Jan Teorell.

During the Age of Liberty the parties were supported by foreign gold, which was divided up among the successfully elected members of parliament, creating an extra incentive to use improper methods to win an election. Fraud affected aspects such as the electoral register, vote counting and the declaration of a winner – in some cases, corrupt mayors decided to send themselves to parliament, even though they had not actually received most votes.

Electoral fraud culminated toward the end of the Age of Liberty, at the election of 1771. At that time the political parties – the Hats and Caps – had grown strong, whereas the bureaucracy had not yet become professionalised.

The next spike in election fraud petitions can be seen in the years around the introduction of the two-chamber parliament in 1866. The political parties were still strong during this period, but in contrast to 1771 the Swedish bureaucracy was now a professional organisation.

“The petitions concerning election fraud were quite different to those of 1771. This time it was more about misunderstandings and ambiguities concerning how an election should be conducted, rather than deliberate corruption to buy your way to power.”

Does this affect the way you see political parties’ role in democracy?

“The parties, of course, are an important part of democracy. Without them democracy cannot function. But the results emphasise how important it is to make bureaucratic reforms in developing countries if you want to address the problem of election fraud.”

What about election fraud in present-day Sweden?

“It is not a widespread problem here, but in the 2010 election there were a record number of appeals concerning ballots, and two ballots even had to be rerun. However, once again the problem mainly concerned neglect rather than an intentional attempt to cheat. One exception is possibly the “election school” set up by the Social Democratic Party close to an early voting station in Örebro Municipality – the municipal election had to be rerun because of it.”

“In Sweden we have long strived to make it as easy as possible to vote, which among other things has resulted in a large number of early voting stations in public places such as squares and shopping centres. The risks entailed when the ballot papers are then sent in for processing have probably been underestimated, but I do not know of a study about the appeals following the 2014 election.”